Context:

For a while now, Samsung has been promoting a “space zoom” feature that was integrated in some of their phones cameras. Their advertisements featured people using their phones as telescopes, zooming in on the moon and capturing images so crisp and detailed they resembled stock photos. Later, an author of a Reddit post conducted a simple experiment revealing that the impressive details on the moon's surface were in fact not captured by the camera, but instead generated by AI. Subsequently, Samsung admitted to using Super Resolution techniques to achieve enhanced quality in their cameras. The moons depicted in their ads, as well as in the phones of thousands of users, have always been partly fictional - the photographs were imbued with the ghosts of numerous images of the moon stored in a database, taken by different individuals at various moments in the past, materializing in a new image that possibly feeds directly back into the same database after creation.

Using the moon story as a launching point and a straightforward guide to action, Studio Pointer*'s research will focus on capturing the ghosts of super resolution in places where they don't naturally belong. With that, they want to get an insight into techniques that are already on the market in various forms, but still kept in the dark. The databases which such AI models are trained on are at least in part “black boxes”. It's no news that the integration of AI in our daily lives is already changing our relationship with truth. Its rapid proliferation both enhances our senses and deceives them simultaneously. What happens when every photo or video captured with one's camera exists in a liminal state, neither entirely fake nor fully real, but always something in-between?

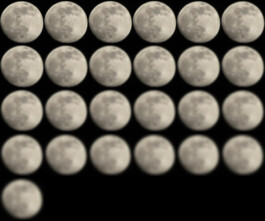

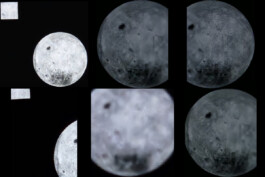

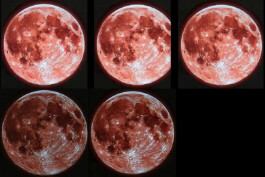

We began our experiments using various images of the Moon sourced from the internet. Our goal was to test the Space Zoom functionality across a range of colors, textures, and surrounding contexts.

To introduce greater variation and evaluate the flexibility of Samsung’s integrated AI, we applied the following modifications to each Moon image:

1. Slight variation in color shade – to test how AI superresolution vision perceives the moon depending on it's shade.

2. Rotation – aiming to test how the algorithm perceives the moon with no texture modifications while rotated to various degrees.

3. Various slight distortions – to see whether a shape or texture alteration affects the moon's recognizability.

4. Various extents of blurring vs. various extents of original resolution decrease.

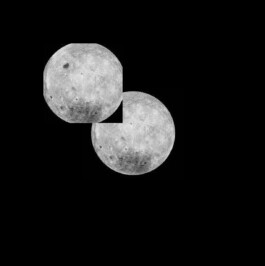

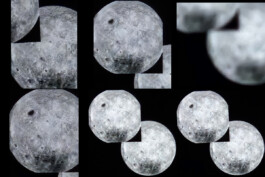

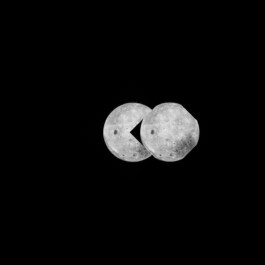

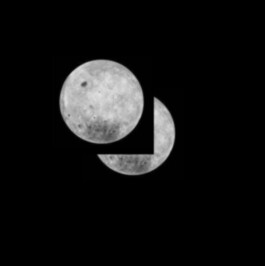

5. Altering the layout of the image itself – to see whether a partially obscured or duplicated image of a moon in the same frame affects the moon's recognizability. Additionally, some images are converted into texture maps, to test the algorithm's ability to recognise purely the shape removed from its original color scheme.

6. Further and slightly more intense distortions and alterations – at times adding a foreign elements to the moon's original texture.

The initial tests were somewhat discouraging. We pointed the camera at a computer screen in a dark environment, but at first, it seemed the AI recognition wasn’t doing much—aside from occasionally adding strange artifacts to the image. This did suggest, however, that some level of post-processing was taking place.

However, after experimenting with different lighting conditions and zoom levels, we began to capture increasingly sharper images of the Moon.

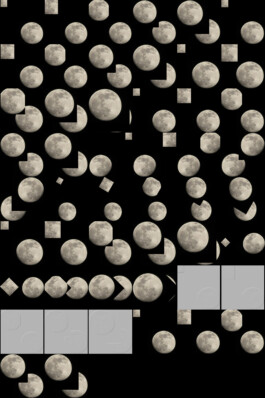

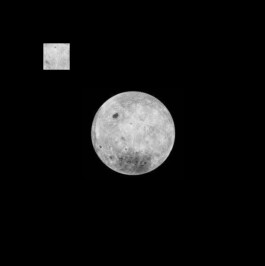

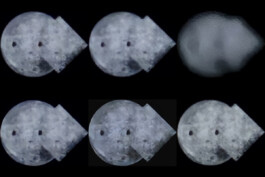

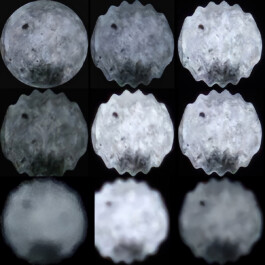

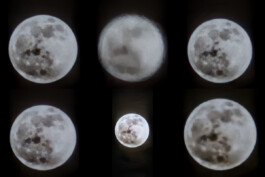

Our initial round of testing led us to conclude that the Space Zoom feature—an AI-driven function evidently trained specifically to recognize the Moon—only activates at the maximum zoom level. After some use, a subtle but consistent shift in camera rendering becomes noticeable once a "moon" is detected. The live view slightly darkens, and the frame shifts a few pixels to the side. Upon reviewing the captured image in the gallery, the algorithm’s impact becomes more apparent: the original blurry, pixelated photo is replaced with a super-resolved version featuring enhanced Moon texture and, in some cases, altered coloration.

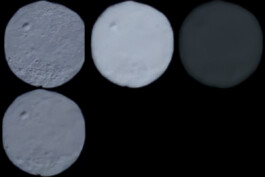

The sequence below shows the views of:

1. Original input image

2. Real-time camera view in maximum zoom mode (zoom x 30)

3. Taken photo before automatic post-production

4. Taken photo after automatic post-production

Interestingly, after the infamous Reddit posts exposed Samsung’s hidden AI integration, the company acknowledged the use of deep learning in general. However, it has never been explicitly stated that the algorithm is specifically trained on images of the Moon or that it enhances photos differently once a Moon is detected in Space Zoom mode.

After further testing and becoming more familiar with the behavior of Space Zoom, we proceeded with a more extensive round of experiments. Once again, the setup was arranged in a dark room, with sufficient distance between the camera and the "moons." Below is a selection of results that illustrate the various ways in which the algorithm successfully recognizes—or fails to recognize—the Moon.

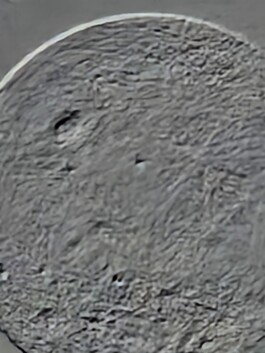

What we found particularly interesting was that Space Zoom was triggered even when aimed at extremely blurry images—provided the setup was still in a dark environment—where the Moon was barely recognizable. In these cases, although the post-processed image did not receive a realistic Moon texture, it was still noticeably altered. The result often featured a new, golf ball–like surface pattern, indicating that the algorithm had attempted enhancement despite the lack of a clear target.

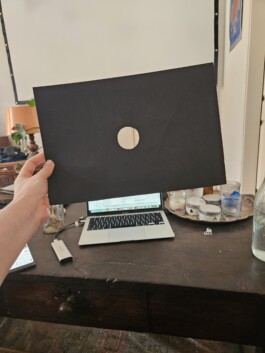

We concluded that, in addition to the Moon’s shape, resolution, and texture, both lighting conditions and the Moon’s immediate surroundings significantly influenced the consistency of Space Zoom activation. Notably, we discovered that masking the rest of the screen improved recognition—particularly in darker environments, but also to some extent in brighter ones.

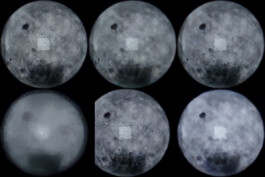

When testing the texture map images of the moon, the Space Zoom was still triggered, yet the results seemed to be less consistent and seemed to reveal some hidden layers of the post-production mechanism.

After testing various original images of the Moon, we concluded that those with darker textures and more pronounced lunar patterns were, surprisingly, less likely to receive effective and sharp super-resolution enhancement.

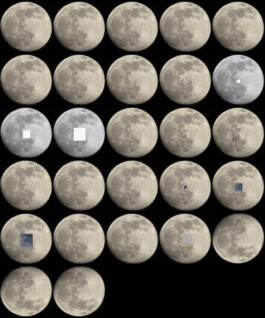

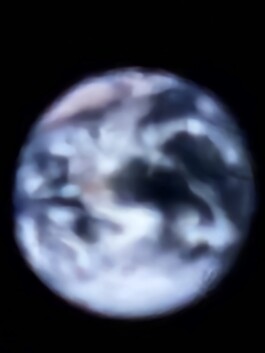

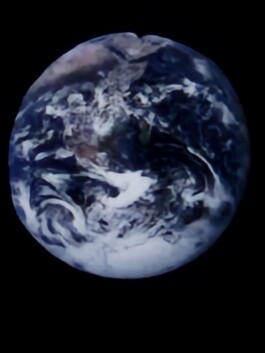

After reaching this conclusion, we conducted additional tests using satellite imagery of the Earth under the same conditions as our previous experiments. Our goal was to confirm the suspicion that the algorithm is specifically trained to recognize the Moon—and the Moon only. Indeed, while some super-resolution enhancement was applied, the results below show that no new texture was added, unlike the consistent enhancements seen with Moon images. Instead, the outcome appeared somewhat watery, resembling a “paint” filter effect in Photoshop.

Similar to the images of Earth, Moon images with more intensely altered colors produced photos where super-resolution was visible but clearly operated differently than on images the algorithm more confidently identified as the Moon.

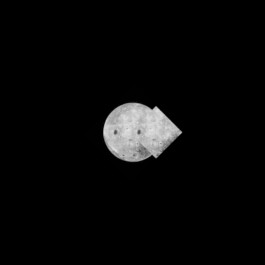

Further testing with less realistic images of the Moon did not consistently trigger Space Zoom. However, after experimenting with the following image across various setups and lighting conditions, we finally began obtaining crisp, heavily post-processed images of the Moon.

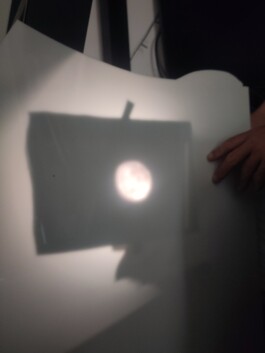

Below are some tests with printed (on a not very new and not very good printer) image of a moon. At first it didn't work very well, yet soon we discovered that with a light source added from behind the printed image, the Space Zoom started recognising it as an actual moon.

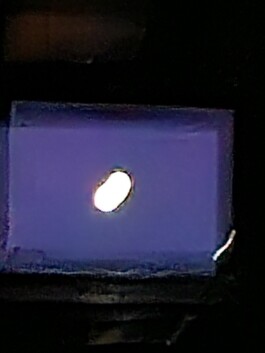

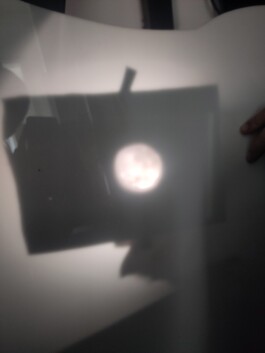

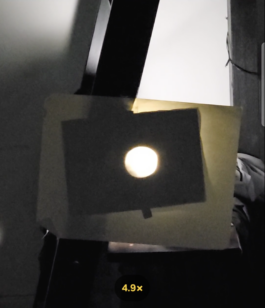

In the next phase, we aimed to recreate the Moon using analog methods. One of our first improvised setups involved a sheet of white plexiglass backlit by a light source, with various printed images placed in between to serve as shadow patterns.

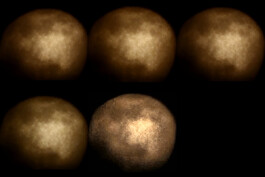

Although the results weren’t as realistic as some photos from earlier tests, Space Zoom was still clearly activated, as evidenced by the distinctive "golf ball" texture imposed on the images.

Below are some additional experiments using a moon-projecting torch—a children's toy ordered online. Although the projected Moon is unrealistic and quite blurry, it is still sufficient to trigger Space Zoom and prompt the AI to hallucinate a much more realistic-looking Moon.

In conclusion, while our experiments focused on a very specific tool—developed for a relatively innocent purpose in itself—the opacity of its inner workings and the lack of direct communication from Samsung have led us to think more deeply about AI-enhanced vision algorithms and how they might be quietly integrated into a range of devices. These span from seemingly mundane yet globally distributed technologies like mobile phone cameras to highly specialized systems with far more at stake, such as military infrastructure.

The infinitely enhanceable image is a sci-fi myth that has long captivated imaginations—well before the advent of widely integrated AI. Today, super-resolution techniques risk reenacting the meme-worthy scenes from '80s and '90s films, where any image can supposedly be zoomed into infinitely, revealing hidden layers of detail that never truly existed. No matter how convincing the results may seem now—or may become in the future—their purpose is to imitate, not to reveal. There is no hidden truth that the camera “sees.”

Through our research, we reached a definitive conclusion: the infamous Space Zoom feature is not simply a general AI-enhancement tool that indiscriminately sharpens all images. It’s a trick—a sleight of hand. The system is trained specifically on images of the Moon, capitalizing on the fact that people around the world frequently take pictures of photogenic moons. As a result, the photorealistic outputs mislead users into believing that the camera is capable of magical enhancement—seeing beyond its own hardware limitations, beyond human vision, and even beyond some professional, high-end equipment.

The recent surge in AI techniques related to computer vision is largely driven by massive, hyper-capitalist corporations whose main objective is profit maximization and market dominance. This often translates to keeping their products opaque—black boxes whose inner workings are never fully disclosed. Unsurprisingly, these corporations lead the industry; they command far greater resources than any smaller, ethically motivated alternatives.

We believe the methodology we applied in this research holds potential far beyond investigating Samsung’s Space Zoom. As black box technologies increasingly shape our everyday lives, similar approaches can be used to reverse-engineer other, potentially more critical systems across specialized domains. Beyond the theoretical and technical understanding of AI-driven tools, such investigations can serve as acts of resistance—efforts to expose what is deliberately hidden and marketed to us as magic.

This research was possible thanks to the generous support of Stimuleringsfonds